Alumni faculty research mentors at UW-Eau Claire set a high bar in chemistry research

As a senior chemistry major with a business emphasis, Erica Akenson was admittedly nervous about doing research at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. But when she got the invitation from a favorite faculty member to join an industry-based collaborative research project, she knew she would accept it.

What she didn’t know was she would be carrying on quite a tradition, as the fourth “generation” in a line of Blugold chemistry research that dates back more than half a century.

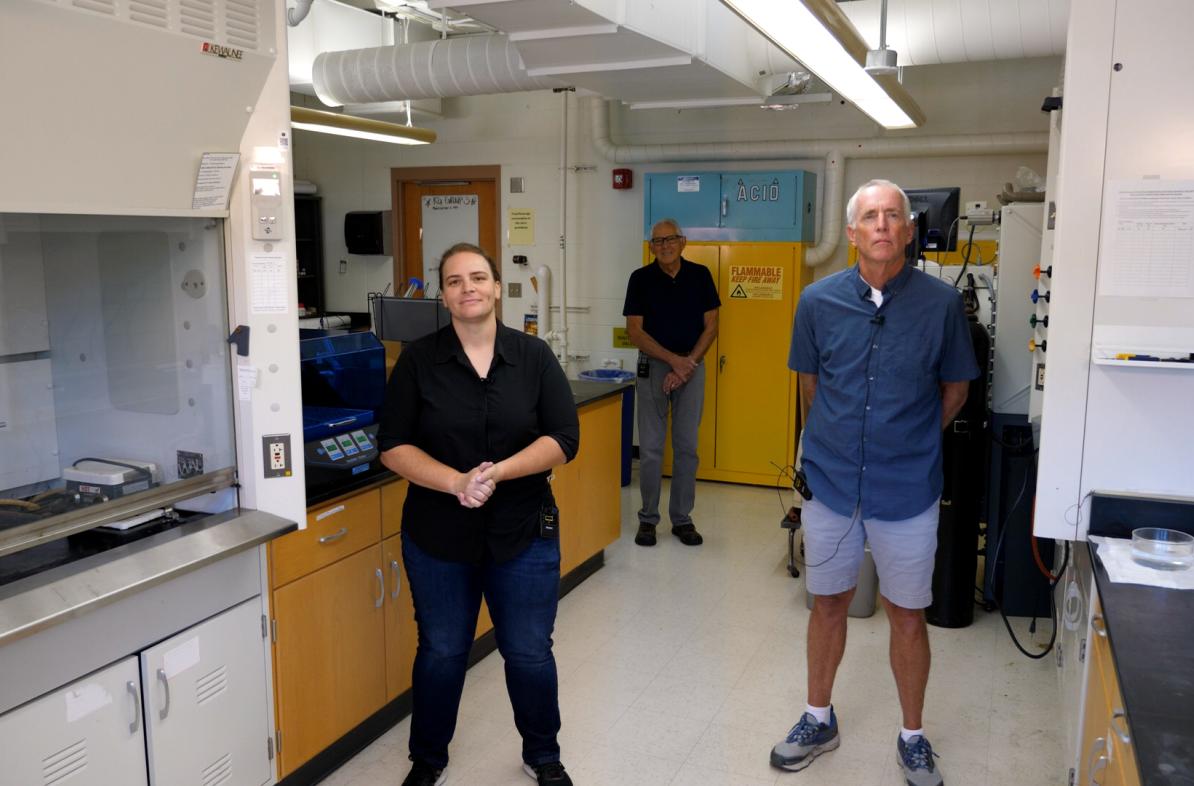

That chemistry tradition includes three faculty members who also happen to be alumni, all of whom returned to their alma mater to share the kinds of research experiences they had as Blugolds with the next generation of chemistry students.

This impressive succession of research mentorship looks like this:

- Akenson’s faculty mentor is Dr. Deidra Gerlach, a 2007 Blugold chemistry graduate who joined the faculty in 2019.

- Gerlach’s faculty mentor in chemistry was Dr. Michael Carney, a 1983 Blugold chemistry graduate who joined the faculty in 2000.

- Carney’s faculty mentor in chemistry was Dr. Jack Pladziewicz, a 1967 Blugold chemistry graduate who joined the faculty in 1972.

The research Akenson is conducting in Gerlach’s lab is a collaborative project with WPC Technologies, an Oak Creek-based company that develops products in the paints and coatings industry.

“I work with their research and development lab to create additives that reduce rust and corrosion. It’s cool to be a part of a 50-year learning history in chemistry here,” says the White Bear Lake, Minnesota, native. “Dr. Gerlach has been wonderful to work with, and she often refers to things she learned working with Dr. Carney.”

While Akenson has long known about the tradition of excellence in undergraduate collaborative research at UW-Eau Claire, she says it is special now to see herself in the big picture of research traditions in Blugold chemistry.

The start of something big

When Dr. Jack Pladziewicz returned to Eau Claire to teach at the university in 1972, he says there was more research going on than there had been when he was student, but research was not part of the institutional culture and internal support was very limited.

“My first research proposal was submitted while doing my postdoctoral work at Stanford, so that grant was awarded by the Research Corporation for Science Advancement in the spring, and I began that project when I arrived at UW-Eau Clare, working with Blugold chemistry students in the summer of '73,” Pladziewicz says.

During the 1970s, according Pladziewicz, the chemistry research climate was what was referred to as “random acts of research,” sporadic student-faculty projects as time and resources allowed. There was no university funding for undergraduate research so activity was limited.

“Laboratories were not set up for major research; they were designed for classroom use,” Pladziewicz says. “There were occasional grants from industry, chemical companies for instance, or rare funding from Research Corporation or the National Science Foundation.”

Over the next 10-15 years, Pladziewicz says that a core of chemistry faculty became much more organized around research and the department received a large development grant from Research Corporation for Science Advancement.

“That grant came with a team of three consultants and matching university funds to develop a real teacher-scholar research program that would engage undergraduates in research that could be published,” Pladziewicz says.

Pladziewicz says that this highly successful award directly led to the “blossoming” of UW-Eau Claire as a center for research, the start of what he says is now a nationally recognized program.

“From the student perspective, undergraduate research became a remarkable steppingstone from a modest Midwestern university to graduate programs in some of the very best places in the world, premiere research institutions in the country,” Pladziewicz says.

Generation two

Case in point, Pladziewicz’s research mentee Dr. Michael Carney took his Blugold chemistry degree and an impressive undergraduate peer-reviewed journal publication to one of the most prestigious institutions of them all — Harvard University.

“I know for a fact that it was my research experience that set me apart,” Carney says about his acceptance to Harvard.

After completing his master’s and doctoral degrees at Harvard, Carney eventually returned to the Blugold chemistry department where he spent 13 years teaching and mentoring research students.

Today, as the assistant chancellor for strategic partnerships and program development, a significant outcome of Carney’s work is undergraduate research. The UW-Eau Claire and Mayo Clinic Heath System-Eau Clare research collaboration agreement, for instance, is focused on increasing access to groundbreaking research opportunities for students, opportunities that lead to real-world outcomes in patient care.

“I understand that incoming students today, like I once was, know nothing about collaborative research; they have no idea what it’s all about,” Carney says. “But like Jack did for me and many others, we take them by the hand and lead them into that world.

“What we do for students here, and what Jack allowed me to do, is to prepare students to enter graduate school a step ahead. Our students go into that setting as functioning researchers, independent experimenters ready to take those challenges to the next level.”

Carney adds that the major difference between UW-Eau Claire and many similar institutions is that hiring practices now fully reflect the undergraduate research culture at this campus.

“During the '90s, this type of student-faculty research spread across all departments on campus and became expected of all faculty,” Carney says. “No longer the ‘random acts’ of research Jack talks about, when I returned in 2000, the idea was ‘you’re expected to do this.’ In fact, we don’t hire faculty today without it first being clear to them that research with students is part of the assignment here.”

Experiencing collaborative research from the faculty perspective has been an inspiring element of teaching for Carney.

“Working with students myself, students like Deidra and others, it has been inspiring to see their growth through research,” Carney says.

“What makes research such a different learning experience from the traditional classroom is that rather than conducting a standard experiment that thousands of students have done before and all arrived at the same answer, with research there is no known answer. Becoming comfortable with not knowing the answer and forging ahead, often as the first person ever to do that experiment? That’s exciting; that’s what sparks the fire in research students.”

Third and fourth generations pair up in the lab

One of the students in Carney’s research lab whose “fire” for science was lit through research was Gerlach, who joined Carney’s lab in the fall of 2005 as part of a student team researching in collaboration with Chevron Phillips Chemicals.

“I was in Mike’s organic chemistry lab, and one day he just asked if I’d ever considered research,” Gerlach says. “As a first-generation student, I had no idea what that entailed, but I joined the lab. It was all exactly what he had said it would be, more experiments, more hands-on work with the chemicals, which is what I really loved.

“It was such an acceleration of the chemistry knowledge, I fell in love with research,” says Gerlach, whose two co-authored studies based on work in Carney’s lab were published shortly after she graduated.

After completing her master’s and doctoral chemistry degrees at the University of Michigan, working at another university and in industry, in 2019 Gerlach returned to UW-Eau Claire to join the chemistry faculty and resume the kind of laboratory learning environment she had come to miss. She now is an assistant professor in chemistry and biochemistry currently working with seven students in her research lab on four projects.

“Coming back to lead the program in chemistry with a business emphasis did bring some pressure — it was big shoes to fill after Mike and Jack. Walking into what had been Mike’s lab space was walking deja vu, in a good way — it felt like home,” Gerlach says. “Mike even teased me, referring to this returning alumni tradition we have going, that I need to start looking out for my replacement as I’m hiring lab students.”

In selecting Akenson to join her research program, Gerlach says she once again leaned on practices of her mentor, a way that she says Carney had of encouraging those students who might not stand out in the typical ways in a classroom setting, but that he identified as having talent that lends itself to research.

“I tend to look at the quieter students, the ones with strengths I think might resonate well in a research setting,” Gerlach says. “Erica was one of those students.”

Akenson says she can now thank Gerlach not only for what is a unique academic opportunity but also for an experience that opened her eyes to a whole new career path she never thought she would find so interesting.

“As the only student on this project with WPC Technologies in Oak Creek, I work one-to-one with their researchers and management. I spent a week there over the summer and got a close look at an industry research and development lab and at quality control practices,” Akenson says.

“This project has really directed me into a much more defined career lane. I’ve seen for myself how my degree can be used in industry. I can see direct connections from my chemistry and business classes at work in WPC.

“I’m finding myself drawn to management, which is a little surprising to me, but goes to show that these research projects are a lot more than running new experiments — they can be a door to a whole new career plan,” Akenson says.

You may also like